In youth participation models, youth and adults form partnerships that enable youth to contribute their ideas, skills, and energy to the shared decision-making process.1 For adults, the key is to determine the type of coordination and interactions that foster youth to make changes, direct activity, and take responsibility for outcomes.2

Youth participation falls into three general models for organizing engagement efforts: youth-led, youth-adult partnership, and adult-led. These models work as a continuum and may be combined to best fit the objectives of youth programs.

Young people are the main spokespersons in youth-led models and look to adults to provide administrative support. Youth are trained and supported to conduct outreach and coordinate projects with their peers. Youth-led organizations make a point to defer to the vision and authority of youth.3

The youth-adult partnership model seeks to establish young people and adults as equal partners in building and leading campaigns and organizations. Youth and adults develop a common agenda without distinguishing youth concerns from adult concerns. Instead, youth and adults share power and authority to plan, mobilize, and educate based upon defined roles, responsibilities, and skills.4

In this model, adult leaders seek out youth as core constituents. Youth carry out the campaign strategies or project tactics that are generally developed by adults. Youth efforts to influence the platform may be minimized in order to maintain campaign priorities. In these cases, youth are positioned as participants rather than key decision-makers.4

Before designing a program, spend some time thinking about which model (or what combination of each model) you will use and consider the following questions:

Hart’s Ladder of Participation provides a visual framework for health centers to think about the current state of youth participation and brainstorm the ideal balance between youth and adults in decision-making. While the balance of youth-adult participation may shift over time, each increase in level of participation generates a higher degree of development for youth.

Montefiore School Health Program (MSHP) is showcasing how youth-adult partnerships can lead to success in the Bronx, NY by enabling youth to take a valued role in their own health care. Youth-adult partnerships, along with youth-led and adult-led, are three general models for youth participation that enable youth to contribute their ideas, skills, and energy to the shared decision-making process.1 These models work as a continuum and may be combined to best fit the needs and objectives of youth programs. As adults, the key is to determine the type of coordination and interactions that foster youth to make changes, direct activity, and take responsibility for outcomes.2 Youth-adult partnerships seek to establish youth and adults as equal partners in building and leading campaigns and developing the organization.3 This collaborative partnership between adult allies in health centers and youth constituents cultivates self-efficacy, empowerment, and skills that youth carry into adulthood.

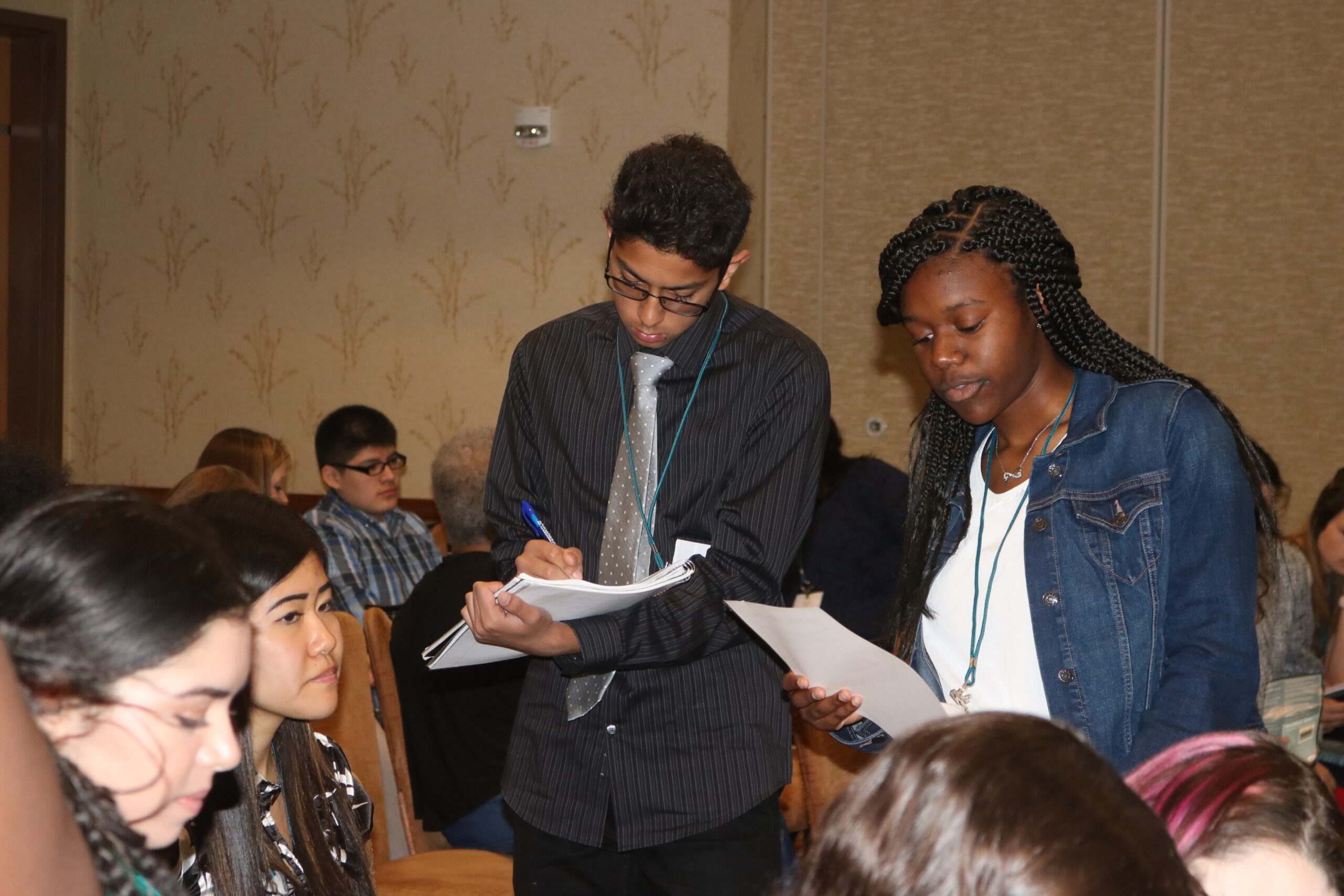

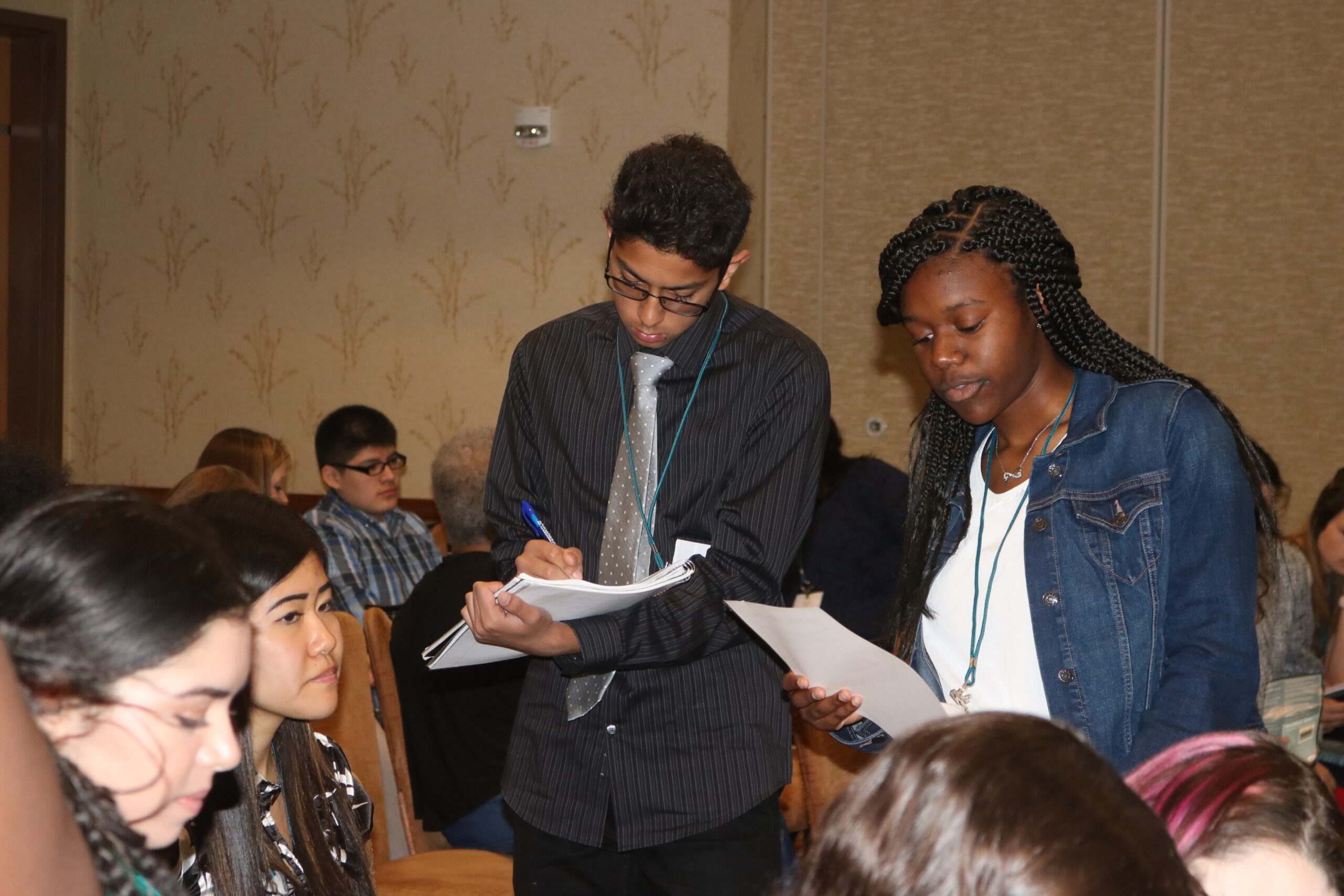

Over the past two years, MSHP, in partnership with Youth Empowered Solutions (YES!), has developed a youth empowerment program that engages youth as both consumers and advocates of their health care. There are three Bronx public high schools with Youth Councils. On each campus, Montefiore Youth Council members complete community health assessments at their schools and use their findings to plan health advocacy projects around the needs of their peers. Each council mobilizes these advocacy efforts throughout the year and convenes annually to send 100 students to the statewide School-Based Health Center Advocacy Day in Albany.

The innovative projects that have resulted from this program highlight the meaningful contributions youth bring to the table in youth-adult partnerships. Some projects have included increasing school-based health center enrollment, planning a school-wide “Consent is Sexy” month to promote sexual assault prevention, and promoting nutritious local vegetables through a monthly “Garden Café” event in the cafeteria. During an interview, Susanna Schneider Banks, Community Health Organizer at The Dewitt Clinton Campus, shared her experience working with the Montefiore Youth Council. She described involvement with the council as an opportunity that allows, “…our students to develop important skills like public speaking and project planning, as well as developing critical awareness regarding health disparities in their communities. Further, this allows students to go from patient to activist and take an active role in their own health and the health of their communities.”